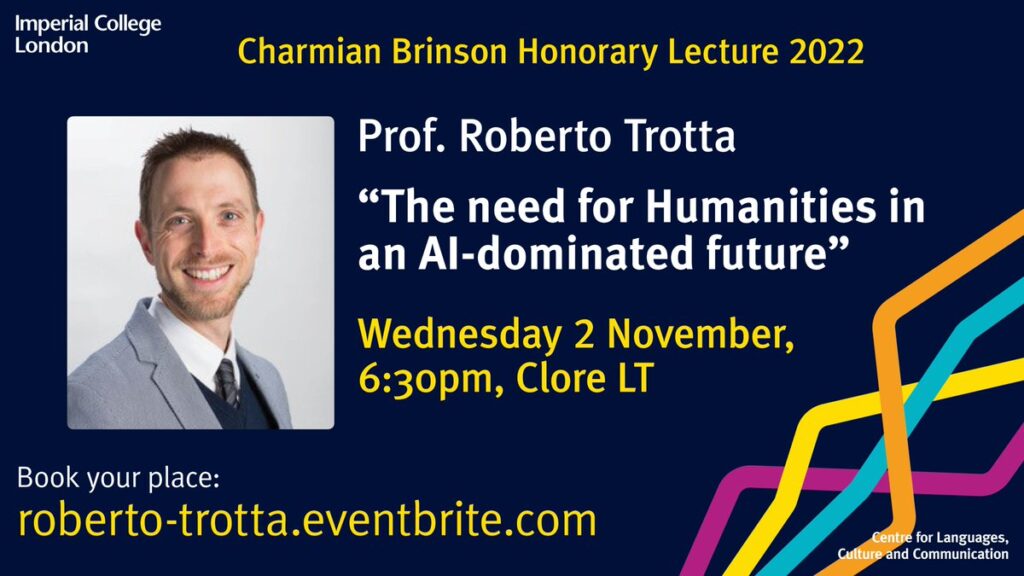

The need for humanities in an AI-dominated future

I was delighted to return to Imperial’s Centre for Languages, Culture and Communication in early Nov to deliver the 2022 Char Brinson honorary lecture on my view regarding the future of AI and the place of humans (and humanities) in it. Here’s a short summary of the main points I raised.

When we hear the words “Artificial Intelligence” (or AI), more often than not our imagination reaches for the Hollywood trope of the Terminator. But the AI that’s changing our lives is of a far subtler, far more pervasive and far more dangerous variety. Largely invisible, it’s being silently weaved into the very fabric of our society, the way we conduct business, how we make and nourish friendships; it’s constantly influencing how we see the world, nudging us into this purchase, that movie, this song or that romantic relationship; and in many cases reinforcing and perpetuating historical racist, gender- or sexual orientation biases.

AI’s quintessential aspect is that of being able to “learn from experience”, an idea introduced by Alan Turing in 1947. An AI system is designed to perform a certain task, but it is not instructed on how to get to the goal its programmer set it. It learns from the examples we feed them, either generated by humans or synthetically, by the machine itself.

This kind of approach has been immensely successful, particularly in image recognition. We now have machine learning systems that recognize all sorts of objects, faces, handwriting, and of course speech, and recommender systems that gently guide our everyday decisions. Proponents of AI claim that they offer an upgrade that raises above human fallibility, inconsistency, ignorance, tiredness and biases. A computer doesn’t have prejudices, doesn’t play favourites, doesn’t get bored and bears no grudges. But there are issues that cannot be brushed away.

Much of the data on which ML algorithm learn is culled from the internet, which means that the resulting trained system displays whatever biases such data may contain, for example gender or racist bias. If such disparities are “baked into the system”, the purportedly “objective” algorithm will strengthen and multiply them manifold into the future. What is often presented as a system above human fallibility turns into a way to automate and disguise, among the billions of carefully optimized neural network weights, that very same fallibility, often in ways that are more difficult to detect because they are only statistical – but real harm occurs to real individuals.

The second question is: what goal should the algorithm reach? Mathematically, different definitions of “fair” are mutually incompatible: we can be fair to individuals, to groups, to categories, but not to all of them at the same time. Even deciding the loss function (which sets the goal that the system is trying to reach) is a task that requires a moral choice, not a merely technical one.

In the words of AI pioneer Joseph Weizenbaum, an MIT computer scientist who in 1966 created a precursor of today’s chatbots and later became a vocal critic of AI:

The relevant issues are neither technological, nor mathematical; they are ethical. […]What emerges as the most elementary insight is that, since we do not now have any ways of making computers wise, we ought not now to give computers tasks that demand wisdom.

The third set of questions raised by widespread use of AI systems revolves around power, accountability and transparency. Internet search results and social media feeds, personalized around our individual interests and profiles, create a bubble that polarizes views – with no governmental nor democratic oversight, as starkly demonstrated by the Cambridge Analytica scandal in 2018. More extreme content is typically prioritized by algorithmic feeds as a way of maximising users’ screen time, the real currency of the digital age – our eyeballs on the screen. It is reckless to leave decisions about issues such as the democratic process and mental well-being of our children to corporations. We are accepting, often without realizing it, to live in a low-grade dystopia.

Just as the taming of the atom gave us both clean energy and immense destructive power, Turing’s thinking machines have the potential to help humankind develop a more equitable and prosperous society, or to amplify current disparities in wealth and power, creating a world in which we sleepwalk into crushing human freedom and agency – a world of automatons, where children swipe before they walk, and where they recognize hundreds of app icons but not a single tree.

As AI is changing profoundly our society, and even rapidly redefining the very parameters of what it means to be human, we find ourselves at a historical juncture where we are groping beyond the material limits of planetary exploitation. After the rainforest, largely lost, after the oceans, filled with plastic, after the poles, melting away hot season after hot season, after the night sky, filled with artificial satellites, Homo Sapiens is turning its extractive attention onto the very essence of humankind. The decision we take today will decided whether Turing’s legacy is a gift to humankind the likes of which we haven’t seen since Prometheus stole the fire from the gods, or an irresistible but poisoned fruit.