Butchery or beauty? Explaining complex science using only the most common 1,000 words in English

A version of this post appeared on the British Council’s VOICES blog on Nov 12th 2014

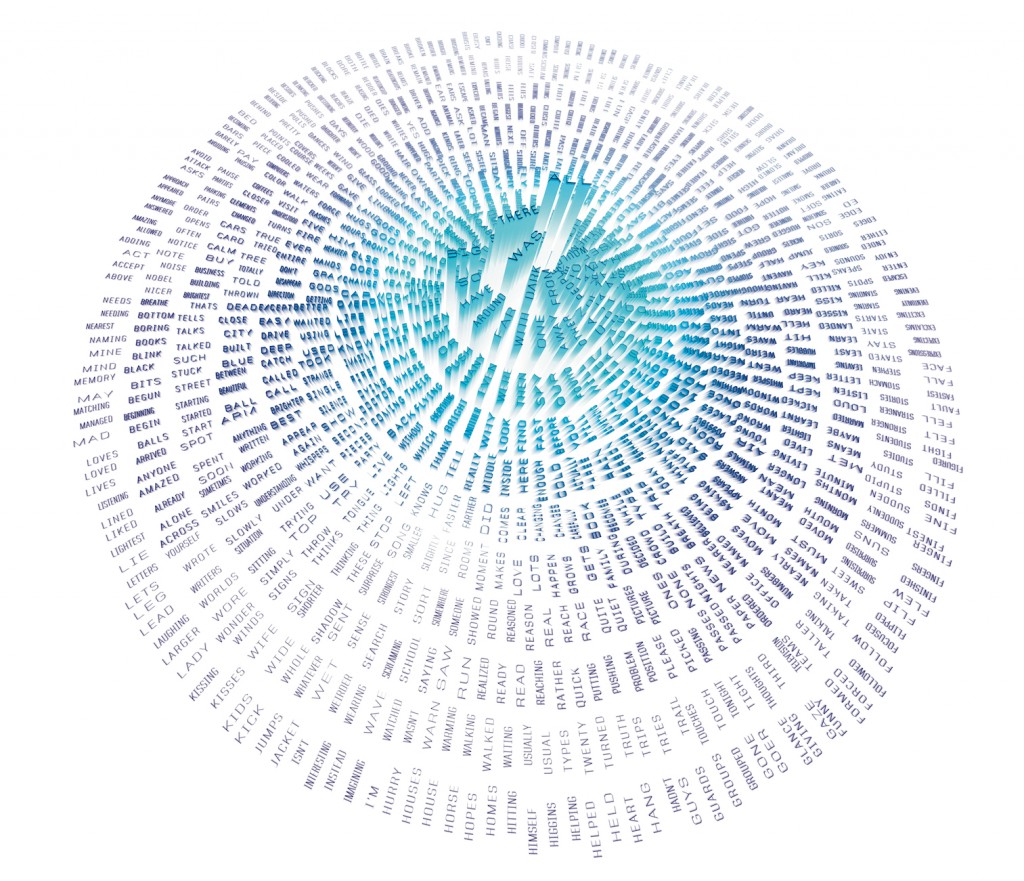

The 707 words used in “The Edge of the Sky”, arranged according to how frequently they occur in the book. Credit: John Pobojewski/Thirst for Foreign Policy Magazine.

Would you try and cross the South Pole wearing only flip-flops? Or row across the Atlantic on an inflatable swimming pool? Or describe the beauty and mystery of the Universe using only the most common 1,000 words in English?

As a professional astrophysicist and a passionate science communicator, I attempt to do just that in my first book of for the public, The Edge of the Sky — All you need to know about the All-There- Is. The book tells the tale of a fictional female scientist (‘Student-Woman’) who travels to one of the biggest telescopes (‘Big-Seer’) on Earth (the ‘Home-World’) to uncover the mystery of the dark matter in the Universe (‘All-There-Is’). We follow her adventure and her thoughts from sunset to sunrise, as she recounts the story of how we came to understand the Universe… and all the big questions that remain unanswered to this day.

The Edge of the Sky pursues the slightly Don Quixote-sque quest of achieving something seemingly impossible with the simplest of means: to rethink our understanding of the Universe all around us with only a handful of different words (707, to be precise). My aim was to discuss some of the biggest questions in science today with a language that is accessible to everybody, from children to adults, from amateur astronomers to the uninitiated, from native English speakers to those who have learnt English as a second language.

The first challenge I faced was to talk about the Universe without using the word “Universe”, for this was not on the list of the 1,000 words. I was shocked to realise that many of the words I really would have liked to use were all of the sudden not available to me: I couldn’t use “galaxy”, nor “particle”, “planet”, “Earth”, “scientist”. It seemed hopeless!

But as I persevered, something unexpected happened.

A new voice started to emerge from the format itself. So “galaxies” became “Star-Crowds”; “particles smashing together” became “drops kissing each other”; “planets” were “Crazy-Stars”; the “Milky Way”, the “White Road”; and “scientists”, “Student-People”. The extremely limited lexicon I was working with created a poetic straitjacket that gave me a new, childlike perspective on the cosmos.

Armed with this Spartan yet powerful language, I found I could tackle all the subjects I wanted, from the Big Bang to the possibility of parallel universes. For example, the expansion of the Universe is explained thus:

She steps outside in the cold night, holding her cup of hot coffee with both hands.

The White Road is beautiful in the dark, clear sky, and, once again, she can not help but be amazed by it all.

It does not matter how many times she has seen this before, or how much she knows about what is out there. The sight of the stars is enough to make her gasp.

”It all seems so still and yet it’s changing all the time,” she whispers to no one.

It is hard to believe that everything out there past the White Road and its stars is running away from us.

Yet, like Mr Hubble found long ago, the Star-Crowds are running away from each other, as the space between them gets bigger and bigger. The All-There-Is is growing with time.

To some, reducing the vast and rich English lexicon to just 1,000 words will be anathema, tantamount to a gross butchery of the language. Others have seen in my experiment a radical shift in the way we communicate science: jargon-free, full of metaphors and imagery, demanding an active participation on the part of the reader’s imagination. By getting rid of all but the simplest of words, the language of The Edge of the Sky acquires the immediacy of folk tales, or perhaps of a post-apocalyptic future when the ‘proper’ words for complex scientific ideas have been lost.

Whether or not I have succeeded in my goal is a question that only my readers can answer. If my book can inspire some of them and generate a new spark of wonder for the cosmos we live in, I’ll be happy.